By Commander YP Marathe, NM, Retd

Having flown HAL produced helicopters right from 1989 till I retired 2008, I have had first-hand experience of the quality of their products, and I wholeheartedly agree with the sentiment that ‘mazaa nahin aa raha hai‘ (not enjoying this state of affairs). I am quite sure that many others flying HAL aircraft would have felt the same way, but it is a good thing that this it is now out in the public domain. I quote the Chief of the Air Staff saying “I am just not confident in HAL”.

One very simplistic way of looking at helicopter production is that the designer designs the helicopter and the manufacturing plant produces that design. At HAL, the RWR&DC is the design house and the factory then produces the finished helicopter. I am not a designer but being a user, and based on my personal experiences, I would like to bring out that HAL’s quality of manufacturing leaves much to be desired. There is a possibility that this post of mine will look more like a list of gripes. All this was actually seen by us in the line and affected our flying. Almost all experiences are personal, bar a few. Towards the end of my flying in the Navy for me, there was a basic trust factor that was missing, and it was standard practice for me to double-check anything that HAL put forward for us. I will list out some examples with photographs. It is said that one picture is worth a thousand words, and I hope that these pictures can bring about transformation and lead to manufacture of safer aircraft.

Fair warning – it is a long read, but then, it is a long story too, so bear with me!

One day in 2007, as soon as I entered the cockpit for an acceptance flight at HAL, I saw a big hole where the Attitude Indicator (the Master Instrument in the cockpit) on the PIC side was supposed to be installed. On inquiring, I was told that this helicopter had been okay-ed by Flight Ops and hence offered to the customer for a final acceptance flight. I then checked with Flight Ops, who told me that ‘yaar, the maintenance team had said they will fix it before offering the helicopter’. I fail to see why any pilot would accept a helicopter for a test flight without the main Attitude Indicator and then clear it for final delivery to the customer. Flight Operations should have insisted on accepting nothing but a complete helicopter, and the Helicopter Division should have offered only a fully serviceable machine for flight. I had to double-check everything, because there might have been some other things that could have been missed out before declaring readiness. HAL was always in a hurry to signal out the aircraft that weren’t really ready, so crew would take longer than the expected time to complete the acceptance. The service HQs would often wonder why the pilots from the squadron are spending so much time in Bangalore!! Now they know.

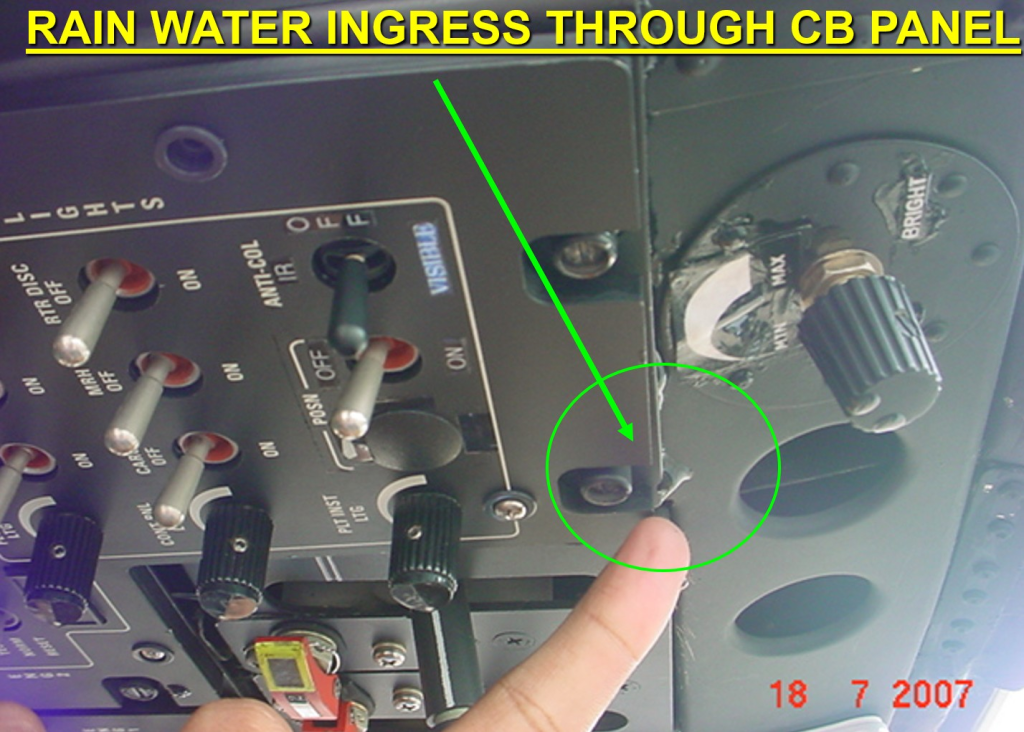

One time, as head of the acceptance team, I had sent the ground crew ahead. They reported that about 20-30 % of the log-cards were not matching with the actual item installed on the helicopter. A log card is a physical card that reflects the installation history of the particular component, because components can be installed across aircraft. When a new component (say a generator or a pump) is installed, its serial number is entered in the log card along with the installation date and component hours. This is essential because each component has a fixed life and needs to be changed / serviced after this life. The log card must travel with the component and reflect the history. On deeper investigation, we realised that HAL had been resorting to cannibalising parts from other helicopters in their inventory, with no records being maintained on the log cards. Thus numbers on the log cards didn’t match with the component serial numbers. This is very dangerous because the component history of installation and repair will never be known, and can lead to accidents. There were also other defects, like the rainwater that would leak into the cockpit, through the overhead CB panel, onto the engine controls on the collective and on the floor. Don’t believe me? Here are some pictures.

At some other time, the unit pilots returned from a flight and found the GPS antenna missing from the aircraft.

Inspection revealed that there were cracks on the mounting. When I called up Flight Ops long-distance from our base, their remarks also left me very surprised– ‘Oh, has your antenna has also flown off?. HAL will replace it.’ My point is, nobody told us so we could have it checked. Something like an Alert Bulletin. Here is a picture. There is a DGCA Airworthiness Directive (AD 013R 1) on this, on my post here

During a training sortie one dark night over the sea I smelled hydraulic oil and asked the pilot to immediately turn towards the base. The rear crewman soon reported that there was oil dripping into the cabin. On return, we found that the reason for the leak was an incorrectly installed crush washer on the hydraulic package (pump/reservoir). This is a pipeline we had never opened at our unit so obviously it was installed incorrectly at HAL itself. DGCA AD 024 also indicates other instances of wrong assembly of some components (highlighted in the blog post here).

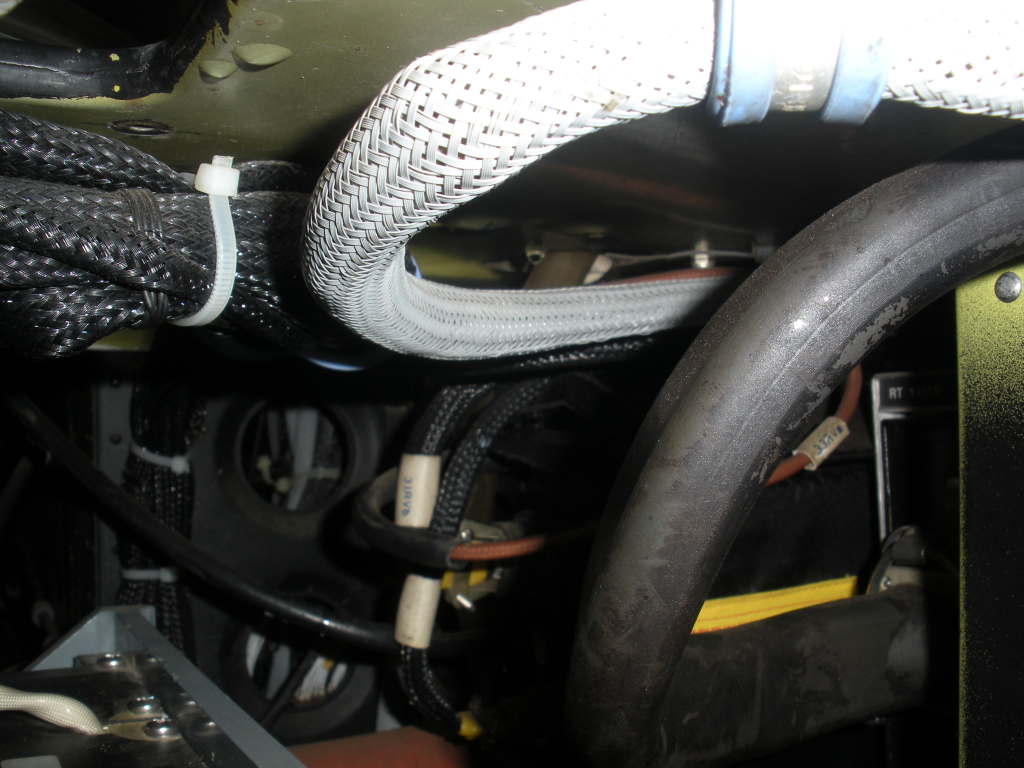

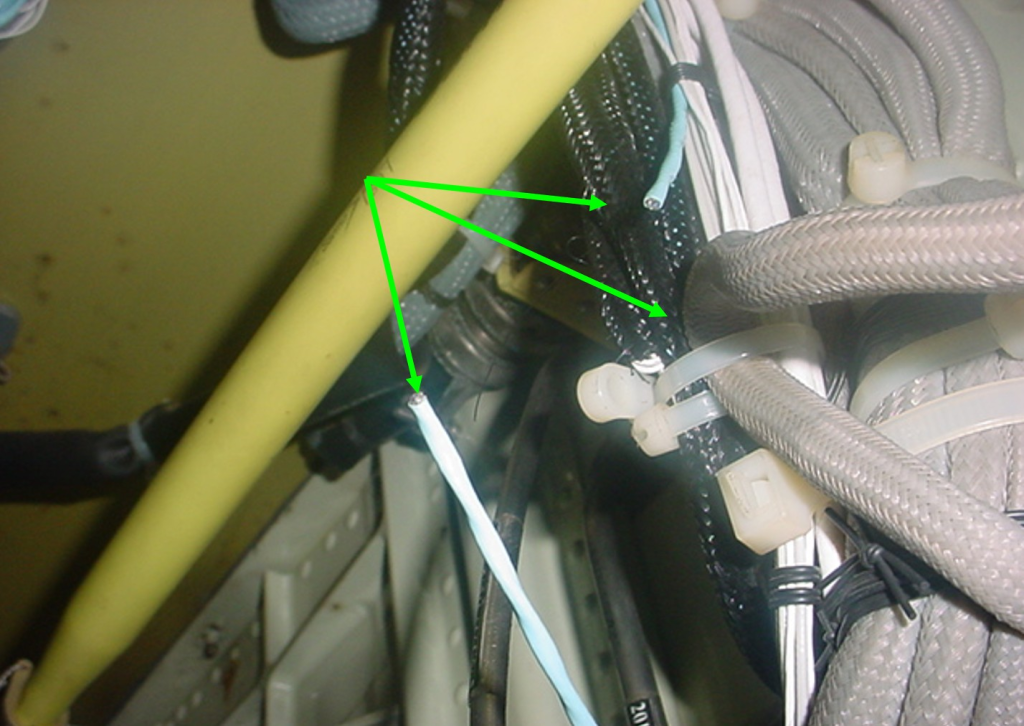

Another time, we could smell something burning during flight and quickly landed back. Our ground crew found that the alternator cables were chaffed on the frame due to vibrations and incorrect installation, causing sparking. There was naked wire and molten metal globs lying on the transmission platform. Since this was under warranty on a recently delivered helicopter, HAL promptly sent the replacement cable harness with workmen who found that the harness had ‘extra length’ and planned on using zip-ties to bind the extra wire (almost two feet of it). Fortunately, before they could complete the installation, the designer who had come to supervise, noticed that the workers were not doing the installation correctly. They did not have wiring diagrams, and hence did not know that the ‘extra length’ was actually meant to route the cable harness around the difficult area. It is no surprise that there was chaffing and failure of the cable on the newly accepted helicopter. Instances like this should have been documented at HAL right then, and corrective action taken.

In another incident in 2009-10 the DC generator cables were attached with connector lugs that seem to have been incorrectly installed. These cables carry very high current of about 1000 amps during the start and so they burnt down over time. The DC generator has a cover on the connectors, and so there is no way to inspect this area.

Wiring and cables were major problem areas too. Here are some pictures of parts of the wiring on our helicopter at the time. The maze of wires randomly pulled can be clearly seen; some wires are taking very sharp bends around airframe structures and also tied with zip-ties all of which led to chaffing.

In many cases wires are routed around sharp corners and also tied up under tension using zip-ties. Here you can see that one wire has broken at the point of zip-tie.

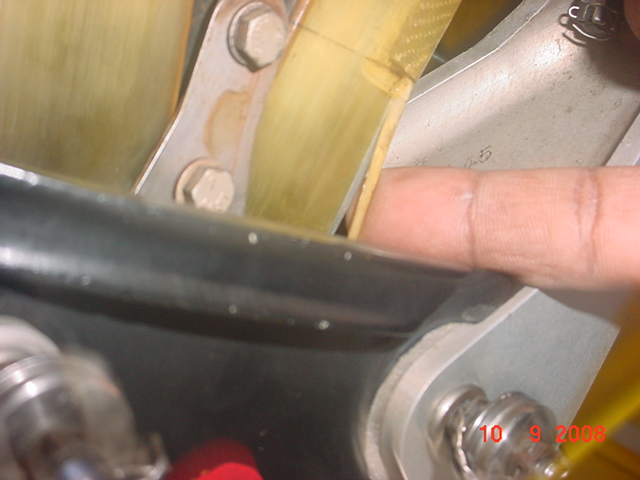

Workmanship always remained a problem. I am putting just one picture here from the helicopter that we received. The hinge is not aligned properly and panels are not matching.

Some time in 2008, we found discolouring on the resin covering of flex beams of the tail rotor blades. As you can see in the pictures below, the discoloured part was also breaking away. TRB vibration was a big problem with the helicopter, and we promptly reported this to HAL. Sadly, nothing was immediately done to fix the problem and we were asked to ‘monitor the area’, that is all!! At some later date, I think they came up with a solution. Here are the pictures. It is very likely that the correct process may not have been followed during manufacture.

An officer from my unit after I retired recounted a tale. During a visit to HAL he was shown the control rod from the helicopter he had recently delivered. The rod was from inside the IDS, and badly bent. He was asked if he had faced any control difficulty during flying, his answer was no. There is a very dangerous trend in most of the accidents and the serious incidents in the ALH, that until a catastrophic failure actually occurs, the pilots rarely feel any control problems. I do not know if the bending/failure of this rod would have been properly documented or investigated. If yes, there should have been difficult questions raised, for which there may not have been answers. All these incidents even then were signs of things going downhill, and should have been addressed at that time.

The last instance I will write about in my personal experience on the ALH was a CPA failure in 2004. I have written about the CPA for further reading here (go to the end). The CPA is a very critical part of the FADEC without which the engine will not be able to function properly, even leading to an overspeed trip. An instance was recounted to me from 2013-14. HAL had installed a CPA backup switch on a Naval helicopter being ferried to Kochi, because there were repeated failures of the CPA in flight (a modification). Despite asking for it, HAL did not give the crew any laid down procedure for using this switch. During the ferry back, the CPA failed and one engine went to idle. The helicopter had to divert to Sulur. That very evening, HAL promptly issued the pilot procedure for using the CPA backup switch. There are four DGCA Airworthiness Directives on the CPA, most of them related to bad quality or bad / incorrect wiring and installation – the reason is clearly mentioned by DGCA, not by me.

There is a helicopter (after my time) IN 7xx that was offered for acceptance. During hover, the MGB oil pressure was low and temperatures fluctuating so the pilot landed immediately. After shutdown, they found that HAL had forgotten to put any oil in the MGB (main gearbox), and it was running dry (pilot cannot see the MGB oil level during walk-around, and has to trust the ground crew when they release the helicopter for flight). The HAL ground crew did not seem overly concerned about this lapse, and they calmly told the pilot that he need not have worried, because the MGB would have lasted at least 20 minutes without oil. Is this the right attitude to have in an aviation setup? Nothing of this would be recorded anywhere, and no corrective actions taken to prevent recurrence.

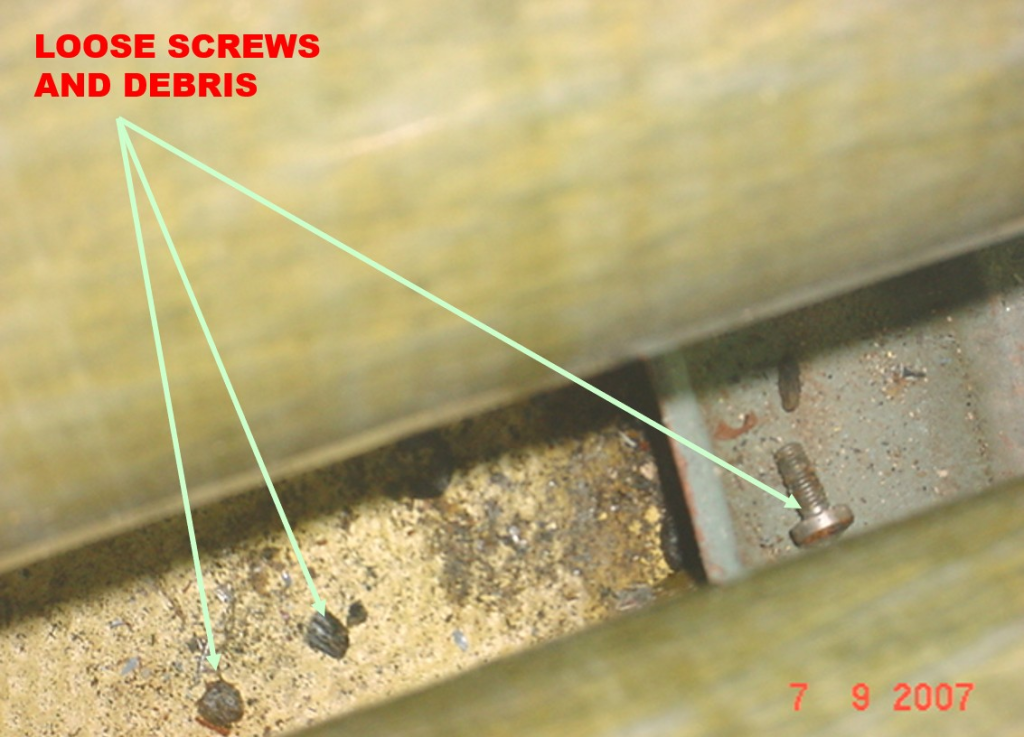

Quality Control – I am fairly sure HAL has a method for quality control. However, when we opened the floorboard for the first time to carry out inspection of the fuel tanks, we found metal debris underneath the fuel bladders. This should never have happened.

We also recovered rag pieces, screws and a ball-point pen from the space below the aft floorboard where the EFG bottles are installed (Bottles are the nitrogen cylinders that blow gas into the floatation gear when activated during a water landing) . A rag piece had remained behind the bottle when the floorboard was installed at HAL.

The most crucial part in all these cases is that the workmanship, and the way the helicopter was put together in the factory was far below standard.

The problem in manufacturing is not limited to the ALH, but even Chetak helicopters had their share of problems with HAL quality and workmanship. In 1993, we were off Somalia, and operating a Chetak recently serviced at HAL. Just as I was coming to a hover on the ship’s deck, the hydraulic system gave way at this crucial point. On opening the hydraulic pipeline we found a rag piece jamming the pump input pipe. This system had not been serviced by my crew because it was a recently accepted aircraft (from HAL) with barely 25 hours flown. We surmised that possibly while servicing the helicopter at HAL some workman had blocked off the hydraulic reservoir or pipeline with the rag piece. This must have gone unnoticed when putting the aircraft back together, and the rag remained hidden until we found it the hard way. The correct way is to use a red coloured plastic blanking which must be removed before reassembly.

There was serious accident on a Navy Chetak IN 4xx in September 2014, where one of the main rotor blades got detached and flew off while coming in to land. The President of the Inquiry went deep into the history of the blade. It was found at NAL that the blade had been worked on at HAL and corrosion treatment near the root was not done correctly. Due to this corrosion spread along the spar and finally the blade flew away in flight. An identical case had happened in a fatal crash about 7 months back in Goa, in which the blade separated about 700 feet on finals at Goa and the helicopter fell to the ground. The Army had a similar case in Bagdogra in Dec 2015.A one time check on all Chetaks revealed 12 more blades had the same problem. Just imagine, there were 12 more such accidents waiting to happen. Quite a horror story. The NAL Report is probably still available for study. There was no information received about corrective actions and anything done to prevent recurrence.

During acceptance of Chetak IN 4xx from HAL in the early 2000s, I had a hover power mismatch from the calculated figure. After many attempts, HAL finally fixed it and I ferried out. During the next 25-hourly inspection at the unit, my technical team told me that the HAL crew seemed to have deliberately misaligned the collective pitch transmitter , so that the cockpit instrument would read the required figure. We then had to do a lot of work on the rigging of the main rotor blades to finally achieve the correct hover pitch in the correct manner, rather than tinkering with the readings. This is just like the 12th standard board practicals, where the experiment sometimes has to be adjusted to get the required readings for the result!!

There is hardly any feedback to the Services about the corrective actions taken at the manufacturing facility. Most of the defects continue to go undocumented. I have said it earlier too that HAL is no stranger to aerospace manufacturing. HAL has been in the aviation industry ‘manufacturing’ everything from helicopters to fighters since the 60s and 70s. It is nobody’s case that all these manufacturing problems are because the ALH is (or was) in development. During informal conversation with present ALH crew I was told that things have improved somewhat, and only little rainwater leaks into the cockpit now. Only a little? Will anyone accept ‘only a little’ rainwater leaking into a personal car costing a few lakhs? There is then no reason for anyone to accept this on a 50 crore helicopter. Period.

The unfortunate quality of workmanship and attention to hygiene in manufacture has nothing to do with aviation but with basic practices that ought to be followed in any manufacturing facility. The automobile industry has very clean conditions in the factories. Their workers have very specific tooling provided, procedures are well laid out, and the environment is quite dust-free. The conditions even in the dealer authorised workshops locally are far better than what were seen in the helicopter factory. The way that aircraft were produced and serviced at HAL did not inspire confidence, even by basic manufacturing standards. I have witnessed the clean rooms in manufacturing lines in the auto industry. I have visited assembly lines at Airbus, Sikorsky and Agusta, and there is no comparison.

The problem has been highlighted most on the ALH, because this was the first really indigenous helicopter produced. The prototypes were flown by the test crew and then the LSP or the Limited Series Production airframes were produced for the customers in small numbers. As the name suggests, the LSP were to be extensively flown by the pilots, and the feedback taken by HAL after many hours of flying. Full scale production should have been started only after all the corrective actions were fully incorporated in the manufacturing. It is unfortunate that many of the jigs, production material and procedures from the LSP continued to be used for the Series Production models, because the feedback was never implemented in time, and SP airframes were rolled out in a hurry. The real danger is that the very same manufacturing ethos and practices are likely being replicated across all the divisions whether in the MiG, Dornier, Sukhoi and the Tejas. There needs to be a detailed audit, complete overhaul and HAL must ensure the highest standards in quality and safety. Some photos of a catastrophic failure of the Tail Rotor Blade are in my earlier post here. We were never shown the report of the first ALH crash. It is only through third hand information that I cannot verify that we were told about other basic issues – the resin bonding treatment rooms were not dust-free as they should have been. Rather than approach the failure that occurred on the Naval helicopter in the mature way, it was brushed under the carpet and helicopters continue to fly without any investigation and preventive action leading to the crash in November 2005

Another possible problem area is the rush to clear inventory by 31 March each year. A careful look at the production figures will reveal a clear bunching up of finished aircraft towards March. This means that production is hurried up in March, with a lot of work being done beyond working hours. This could lead to shoddy work, glossing over safety protocols and procedures thus leaving no time for quality checks or re-work. Pilots are pressurised to accept the helicopter in whatever condition it is offered in March. the only way out of this is for HAL to positively ensure a delivery schedule that is evenly spaced throughout the financial year.

I am fortunate to have seen the design and testing facilities at HAL first-hand. All the dynamic components are put through very rigorous testing upto the limits set by the designer and more. Blades secured on hydraulic rigs are continually tested almost till breaking point. All the samples – control rods, linkages, beams, gearboxes are also tested in a similar manner. It is quite clear that the design and testing teams are doing a very meticulous job and that the specific parts put on these rigs had passed these stringent testing standards. The testing facilities encompass a very impressive setup. My interaction with individual members of the design team were always very rewarding. I found them to be a very knowledgeable set of brilliant people all motivated to produce world class helicopters. One wonders then that, despite all this, why these helicopters continue to crash, and that too with relatively low time on them even after parts that have passed rigorous testing.

One possibility is that many of the failures are caused by the shoddy workmanship and not a faulty design. even the DGCA has said in their ADs that some incidents are attributed to incorrect assembly, wrong wiring, correct process not followed etc. If the shop floor does not take care to make components correctly or put them together the way the designer has planned it, then the fault lies not in the design. We will never know, because there are no records maintained, and in many of the ALH crashes, it might be very difficult to pinpoint whether the crash caused the component failure or the other way around. I quote a modified line from an aviation movie – The mind is writing cheques the body can’t cash.

Is there something that can be done?

- Pause manufacturing, and do a thorough audit of all the manufacturing processes. This includes tooling, work-flow, clean areas, precautions and the like. If necessary, take inputs from automobile and other manufacturing industries even if they are non-aviation.

- Ensure that there is a plan for continuous work completion and production against a time line. Do not allow production to pile up till the year end; there should be a monthly target for production, without bunching up to the last week of each month. This will avoid work being done after normal working hours and too much in the month of March.

- There must be a system for the customer to report to HAL each and every defect in the field, whether minor or major. All component changes or rejections must be studied and documented at HAL for allied reasons. HAL must honestly report each and every defect and component failure to all other customers regularly. The data must include information like, when the defect was found, component hours etc, and mainly an analysis from the user as to the secondary effect of the failure. For example, the CPA failure will possible lead to an overspeed on the engine. There must be a central agency to independently collate all this data, analyse trends, and determine if there is a design defect or quality issue in manufacturing or in type of operations. It is very possible that failed parts were not manufactured properly or were installed incorrectly. Analysis of the failures must be communicated to all customers and be used to improve product quality.

- There are cases where even after suffering a serious failure an aircraft survived with just a hard landing. For example, it is learnt that there are Army and IAF helicopters that have dropped to the ground from hover due to failure of the control rods. These will never get classified as crashes or accidents, but they are in effect like an accident, and would have become a statistic had the takeoff been continued. A CPA failure due to bad workmanship must also be classified as a serious incident, under manufacturing or design or both. This process of documentation is extremely important in any new helicopter or aircraft, and HAL must implement it right away for the Tejas and also the LUH. In fact, it would be good to start something like this for all their products even now, with honest reporting and honest analysis. It is only when the (manufacturing) house is fully in order can we realistically come to know the real cause of many of the aircraft accidents, whether it is design or manufacturing.

- The services should stop accepting helicopters under any kind of concession in critical areas. One example is the blade folding of Naval ALH. The requirement as per NSQR was 3.5m folded width. HAL had taken a concession even before delivery and has never provided a helicopter with less than 5.4 m width, after two decades of flying the helicopter. This applies to all HAL developed aircraft. If, as brought out recently the LUH indeed has a problem with basic handling and with autorotation then the services should not make a commitment for this helicopter in any form whether LSP or otherwise, until all these problems are completely eliminated. Unless this is done, there is no pressure on the OEM to produce aircraft that meet the stringent requirements of safety and reliability.

This is not to say that other aircraft manufacturers always had a smooth run during development. Yes, there were many accidents and design issues. The difference is the approach to these; most OEMs have a greater amount of transparency and positive attitude to try and get over the problem with a permanent solution rather than short fixes. Look at the way Leonardo fixed the problem with the tail rotor of the AW169 after the spectacular crash in Leicester City in Oct 2018. They didn’t start investigation by blaming pilots or maintenance. The AW169 today is a highly successful machine all over the world although Leonardo is facing a lawsuit of over GBP 2 billion by the family of the owner that died in the crash. Is this the only way that HAL will start getting things in order, a lawsuit?

If the manufacturing does not play along with the designer’s designs, can you really call it a design fault? How do you determine what is the failure factor here? I do not have the answers, but this is something that only a deep study will reveal. I am told that quality and manufacturing have improved somewhat in the more recent aircraft, which is a good thing. But if this is so, why are there still more crashes on the Mk III models? There is more information on a separate blog here about the recent unfortunate crash on 5th of January of the Indian Coast Guard ALH at Porbandar.

It is also time that something is done about the absolute monopoly of this aviation behemoth. Only then will there be real competition, and a real need to improve everything for real customer satisfaction. Imagine if today, we were still stuck with the choice between an Ambassador or a Premier Padmini, because no other car manufacturer was permitted to set up shop! This is exactly the condition we find ourselves in.

There must be alternate sources of aircraft manufacturers, and the customer’s choice must be based on the best available option there. Initially it will definitely mean contract manufacturing, because there is a very steep learning curve. There is a lot of aviation production already originating in India. Tata-Boeing aerospace has recently delivered the 300th fuselage for the Apache helicopter, for example.

In any commercial organisation, there is accountability and there are financial bottomlines. Any worker or manager found not doing the task properly will find that his contract is not renewed. Accountability must be ensured in any manufacturing facility whether PSU or not. Any non-performer must not be allowed to continue. If things are not fixed in time, even the prestigious Tejas project will have the same kind of defects and problems because of workmanship and quality. It will be the same for the LUH production. We must not fool ourselves into believing that the Services ought to support the PSUs at all costs. We may forgive HAL, but will the enemy forgive us in a war is the question. In the now public video even the Chief of the Air Staff has opined that HAL is not in Mission Mode while sitting in an HAL Tejas during the Aero India 2025.

This government has taken the right steps in bringing in private companies into defence and aerospace, the biggest example being the contract manufacture of the Airbus 295 for the IAF. Tatas have taken a big leap on their own by setting up the H125 assembly line as well. Unfortunately there is a lot of investment in all these setups and it is difficult to sustain this without some kind of assurance of numbers that can only come from Government or defence orders, at least to start with. Even Agusta / Leonardo started off as a contract manufacturer for the Bell models long back, and has now come into its own. That is probably the way to go.

It cannot be business as usual at HAL, we can no longer accept the shoddy workmanship that we have seen for so many years, that cost us precious lives and expensive aircraft. Generating sales by forcing the Services to accept below-standard aircraft just to fill in the order books is totally wrong and ineffective in the long run. If a product is really good, then order books will automatically be full from willing customers to purchase a helicopter that makes good business sense. Civil operators cannot afford the amount of inevitable down time when you fly an HAL product. It is obvious that no commercial civil operator has enough trust in any HAL product to ensure the required flying and stay in business. The LUH was an excellent opportunity to enter the lucrative single engine commercial market, but sadly there is no interest there. Pawan Hans contracting for the ALH is and exception because both are PSUs.

I bear no malice or ill-will towards HAL or the ALH. In fact, all the time we flew the ALH for proving it in the field, we were very proud to be the chosen ones to undertake this task. When the helicopter is serviceable, it is a wonderful machine to fly and has served well towards saving lives, supplying the high altitude posts and conducting rescue. Sadly, HAL’s pigeons have come home to roost, and many innocent lives are being lost in disastrous crashes. I can’t even even imagine the terror experienced by each of those pilots as they fell towards the ground, holding a completely ineffective set of controls, desperately trying to recover from the ever increasing spiral taking the helicopter to their certain death. Whether all this is due to design or manufacture or workmanship hardly matters to the families grieving for their loved ones.

HAL needs to urgently take the right steps (whatever the cost) to prevent more accidents. HAL owes it to all those victims of crashes on HAL built aircraft to rise above it all and ensure safety and reliability in its products.

I end this with a prayer for all those lives that have been lost due to issues in workmanship, quality or design. I sincerely hope that there is someone listening out there, and that change for the better. I will be the happiest person to see HAL successful, commercially and technologically.

Jai Hind.

The author is a helicopter pilot, Qualified Flight Instructor and has about over 6,500 hours of flying. He was the Flight Commander of the first Naval ALH flight and has adequate experience in taking the ALH through all the paces required for Naval requirements. After retiring from the Navy in 2008, he has flown commercial offshore and ashore flights. His views are personal. This post first appeared on Cdr Marathe’s blog here, and is reproduced here with permission. Cdr Marathe has previously written for Livefist here.

HAL needs to shed the Local recruitment of workmen technicians and engineers which must be a all India selection with a sizeable no of Foreign engineers , supervisors and technicians selected on contracts to improve work culture standards of production and shop floor discipline . New generation 7 axis or 9 axis CNC machines , 3 D designing of parts and robotic assembly must be there for fit and finish . Indian private strategic aero companies must be involved in manufacturing assembly repairs and deep maintainance of the Choppers . The helicopter division needs to be separated from fighter and trainer division with separate management financial control and discipline of shop floor and production .

Any responsible and honest person must first address the most fundamental question – What is HAL?

Bunch of privileged class Baabooz that control it from the corridors of SB?

OR Board of Directors (Most of whom have no or little stake?

OR The Designers, Engineers… the class that delivered Bharat the very first Supersonic Combat Aircraft HF24 Marut (destroyed by Sarkaari Tantra, Greed and Importeomania)?

OR the highly politicised Trade Unions of largely non-performing staff recruited for variety of unscrupulous reasons except actual need

Please decide first before blaming HAL