US President Donald Trump’s offer to sell the fifth-generation F-35 Lightning II to India has raised a few eyebrows in Indian defence circles, sparking intense debate about its feasibility and implications.”

Most critiques of the F-35 offer to India have focused on strategic autonomy. Given how the United States maintains tight control over F-35 operations even among its closest allies, should India make the sharp end of its combat aircraft fleet vulnerable to American political whims?

That is a valid question, but this essay takes a different track. Instead of the geopolitical angle, it examines a more fundamental issue: does the F-35 even fit into the Indian Air Force (IAF) from a technical standpoint?

The Shift to Network-Centric Air Combat

Modern air combat is all about connectivity. In NATO air forces, everything is linked—aircraft and surface systems detect and track targets, and that information flows seamlessly to pilots via secure data links.

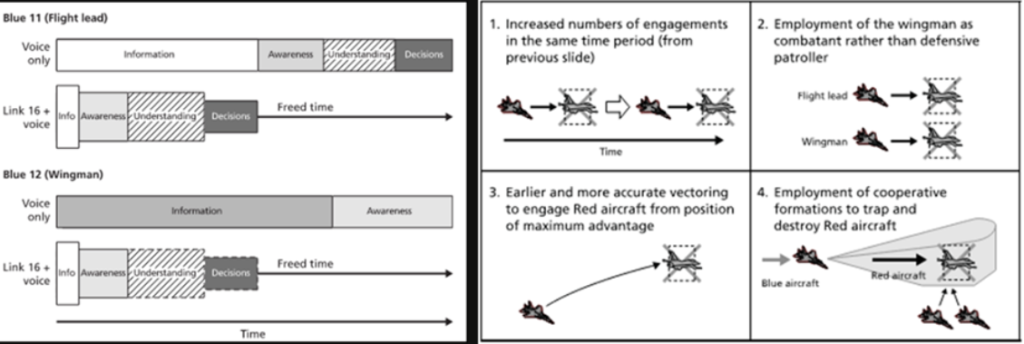

In the mid-1990s, the US Air Force conducted a study to evaluate how networking affects air-to-air combat. They pitted packages of F-15 fighters against “enemy” F-16s in mock engagements. Half the F-15 packages relied only on voice communications to exchange information about enemy aircraft positions and tracks. Their performance was compared against the other half—which used the Link 16 data link. This system allowed the F-15s to receive air track information from nearby fighters and AWACS, displaying these tracks on a screen with high accuracy. Targets detected by any aircraft in the package were automatically transmitted and displayed in all aircraft, enabling improved strategies and tactics to gain an advantage.

Over 12,000 engagements, the Link 16-equipped teams were found to be over two and a half times as effective as those relying on voice communications alone. The conclusion was clear: seamless, automated information sharing vastly improves mission effectiveness, while voice communications are slow, prone to errors, and cognitively demanding for pilots.

The study was an early demonstration of what we now call Net-Centric Warfare (NCW)—where real-time information sharing enhances situational awareness and decision-making.

It is in such a fully networked environment that the F-35 thrives, sharing and fusing data with other platforms—fighters, AWACS, ground radars, and command centers— enabling them to work together as a single, intelligent force rather than as individual units.

The Indian Air Force’s NCW System: A Work in Progress

The Indian Air Force isn’t at this level of integration yet. The IAF has often been described as operating like two or three different air forces; and there is some truth to that. Different aircraft, radars, and command systems don’t always talk to each other the way they should. A perfect example is the India-Pakistan air skirmish that occurred in the aftermath of the Balakot airstrikes in 2019. Fighter controllers were still using unencrypted voice calls to communicate with pilots—hardly ideal in a 21st century conflict.

Since then, the IAF has adopted the Israeli BNET-AR software-defined radio and integrated it on its aircraft, but a major question remains: does a common operational data link actually exist? Can a mixed package of Mirage-2000s, Tejas Mk-1As, and Su-30MKIs, directed by a Netra AWACS, automatically share track information? Can this information be exchanged with the Integrated Air Command and Control System (IACCS)? Or are IAF fighters limited to using the BNET for secure voice communications among aircraft acquired from different countries?

The F-35 as a Lone Wolf

Even if the IAF were using a data link, a second challenge would arise: is the F-35’s data link compatible with the standards used by the IAF? Can it seamlessly integrate into the IAF’s broader network? If not, would the United States government and Lockheed Martin permit the necessary modifications to enable interoperability with an entirely different communication system? Given the stringent restrictions the US places on the F-35’s software and hardware, any such integration would likely require extensive negotiations—if it is even allowed at all. Without this, the F-35 risks becoming an information silo within the IAF, flying stealthy but largely blind to the bigger air picture.

This problem isn’t just about the F-35; it applies to other advanced jets like the Rafale too. The issue isn’t the aircraft, but the ecosystem they are flying in. Advanced fighters are designed to be information nodes, not just combat platforms. Their ability to gather, process, and share battlefield data is what makes them truly powerful.

Right now, the IAF doesn’t have that kind of ecosystem. Instead of simply buying more planes in pursuit of “squadron strength”, the IAF would be better served by investing in the infrastructure and systems that enhance the effectiveness of its existing fleet. This includes expanding AWACS and tanker capabilities, improving airfield infrastructure, integrating electronic support measures (ESM), and, most critically, implementing a robust data-sharing network that allows its diverse fleet to operate as a cohesive force. In such an ecosystem, even a nominally less advanced fourth-generation fighter like the Tejas could contribute more effectively than a lone wolf foreign fighter.

Mihir Shah is a mechanical engineer who tracks military and aerospace issues closely. He contributes to to LiveFist, Pragati Magazine, and Bharat Rakshak’s Security Research Review. Follow Mihir on Twitter here.