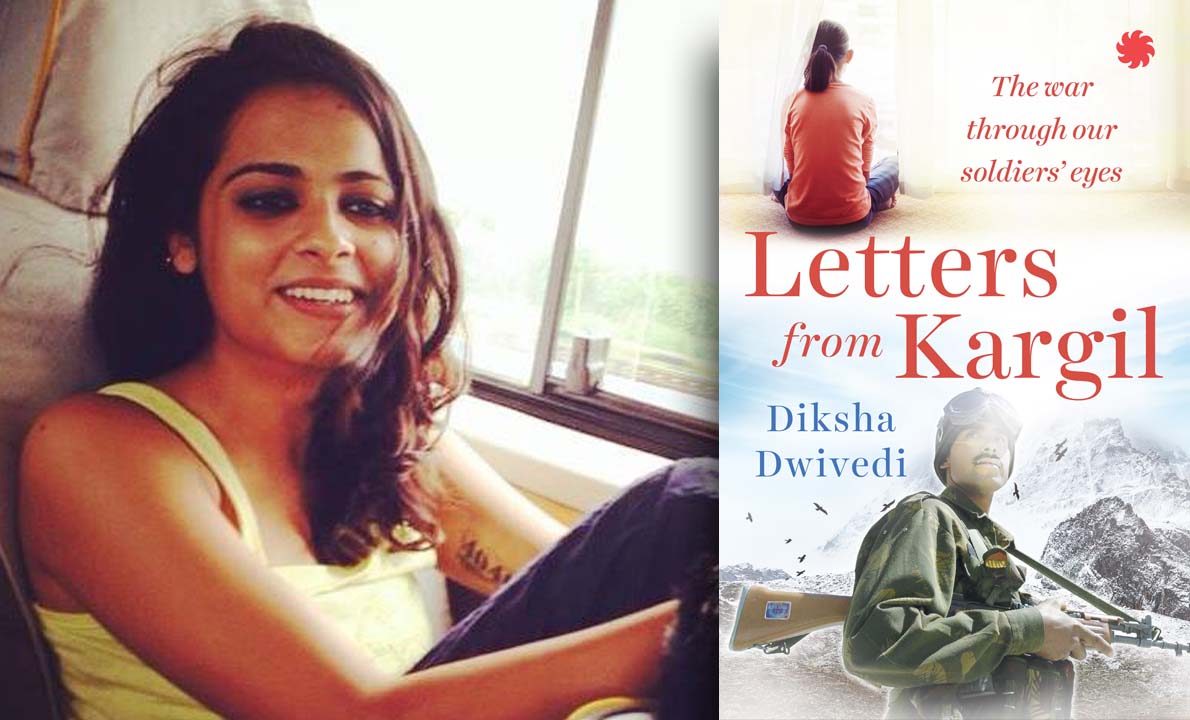

You know a memoir is about to drag you out to sea when the writer ushers you in with her most painful, delicate memory. In Diksha Dwivedi’s new book Letters From Kargil: The War Through Our Soldiers’ Eyes, it is a veritable punch in the plexus:

I had never seen so many people at one place in my life. My father’s five-foot-eleven-inch-long body was placed carefully in the gallery in front of his father’s room. This was the last time we were going to be able to feel his skin, see his face. I couldn’t go close to him. As soon as the plastic sheet around him was unwrapped, I glimpsed his face from afar. It was covered in white powder, which made him look ghostly. Terrified, I ran to another room. That’s the last memory I have of seeing my valiant father, my hero. I didn’t salute him, I didn’t try to stop him from being taken away; I simply found an escape. This eight-year old coward was a soldier’s daughter. I have never forgiven myself for that day.

It isn’t hard to believe that Diksha, who was eight when her father Major Chandra Bhushan Dwivedi, an artillery officer with the 315 Field Regiment was lost in the Kargil War of 1999, has spent the last two decades first understanding, and then coming to terms with that memory. In every way, it is that volcano of a past ‘shame’ that appears to have compelled the writer to put her head down and see about giving a few ghosts some belated peace. The result is this splendid little book, where Diksha, convinced that researching the breadth of India’s well-documented first television war wouldn’t quite tell the story she needed to, has decided instead to be a messenger between two worlds riven by that war. In a series of letters from soldiers, including her father, to their families — numbing, hilarious and terrifying in turn — Diksha employs the familiar narrative of a war story told in messages to investigate that most unrelenting of sentiments: loss.

The letters range from the deeply personal — as the many letters from officers to their wives or children — to the very illuminating, as with the several letters by young officers to their siblings or parents just days before major events during the war. For instance the utterly numbing letter from young Captain Neikezhakuo Kenguruse of 2 Rajputana Rifles to his brother in Nagaland only a few days before the officer’s famous final mission to secure the Three Pimples ridgeline in Tololing. It is a rare letter in this book that doesn’t leave you suspended for many moments between the worlds of the living and the dead.

Letters From Kargil is a painful, understated tapestry on a conflict that never should have happened. Historians and military enthusiasts will find wonderful nuggets that add texture to the stories they’ve heard from the heights. One doesn’t remember a gentler, more heartfelt meditation on war in recent times.

Livefist spoke to Diksha Dwivedi about her new book:

In the nearly two decades since Kargil, do you think India values its military heroes less or more?

With every year, it has gotten better. Till last to last year, only a few (and same) names did the rounds of media and although it played the part of representing all war heroes, somehow I always felt an extra effort could be made to talk about unheard stories. I’d consider myself and my family lucky that we have the means of putting out my father’s story, but there are so many of those soldiers’ families living in villages, who have nobody to tell their stories. So to answer your question, it’s getting better yes, but it’s also dependent upon what’s fed to you and then you follow up. Like I wrote daddy’s story in 2015 after waiting for 16 years to see his or his regiment’s name in some corner of media if not a whole page.

India hasn’t officially declassified its major war histories. Do you see that as a problem?

I hope and believe that major war stories become a part of history books in schools, including the Kargil war, it would be the best way to pay tribute to war heroes. It will also educate the future generations about the consequences of this phenomenon called “war” so they don’t find it as easy to say “war is needed” and if they still do, they at least will be giving a mindful opinion. So I don’t know if I see it as a problem but I do see it as a gap.

Do you sometimes wonder if civilians can ever fully empathise with the families of military personnel?

They can’t and it’s unfair of us to expect that from them. First we have to make an effort to explain to them what being a military personnel’s family feels like. Letters From Kargil is my tiny contribution towards that, I wrote it keeping them in mind always, every step of the way.

If you had the country’s new Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s full attention for five minutes, what would you tell her?

I don’t need five minutes, I’d just tell her come up with a peace strategy. And till that’s possible, and it might sound selfish, it has come to my mind more often than not that what’s the value of a soldier’s life because of the low pay that’s usually justified by the perks and ration, which I think are certain things that are available in every profession these days. So should they not be paid decently (or more than most professions) for waking up every day to die for the country by the ‘higher the risk higher the return’ theory? Last thing would be, invest in defence more liberally, they and we need it more than anything till the day we’re able to boast of world peace. Also, educate this and the future generations about defence, war, consequences etc. It’s important.

The one thing you would change about the Army if you could.

If I had a magic wand, I’d wipe off the need for an army in this country or a war in this world.

The three things you remember liking most & disliking most about growing up an Army child.

I loved the uncles (daddy’s unit officers and course mates), bachelors especially. They were the coolest humans we knew as kids! The mess parties that kids were not allowed to attend, which meant all kids in one room with lots of movie DVDs and snacks, and eventually dinner. Such innocence is always missed. The respectable lifestyle, safe environment. I have an endless list of things I absolutely loved about growing up as an army kid, I have my upbringing to thank for everything I am or I will ever be. The only thing I can remember disliking is the heavy price that had to be paid for your family serving the country – stay away from family and death.

Letters from Kargil is published on Juggernaut http://bit.ly/2j6Xm