By Commander YASHODHAN MARATHE (Retd.)

The heart-wrenching sight of the smoke billowing from the crashed Indian Coast Guard (ICG) helicopter at Porbandar on January 5th, 2025 brought back to my mind the struggles we had with HAL when I was commanding one of the first two ALH Flights of the Indian Navy.

This particular crash seen here in the picture has been attributed to a rare transmission defect as per some news reports.

The term “rare” means ‘not happening very often’. In so many of the ALH crashes, there is a new ‘rare’ defect each time, so the term ‘rare’ loses its meaning. So many ‘new-and-rare’ defects on this helicopter, more than 20 years after it was handed over to customers, can only point to an inherent problem with the design or the manufacturing.

HAL has a responsibility to deliver machines that are safe, efficient, and that meet the product specifications. The ALH however, is sadly lacking in the safety and efficiency department. HAL is also a listed company and has an obligation to the shareholders to come clean with the problems. There have been close to 25 ALH crashes in India since 2005, out of the 340 aircraft produced. Many of these crashes are due to a technical failure. Some, although attributed to pilot error, might actually have a design or manufacturing problem as the root cause. This Porbandar crash has been attributed to the swashplate. Those who want to read about swashplates can click here and here for some videos.

The ALH has a basic problem with vibration and control forces. The ARIS (Anti Resonance Isolation System) that was designed to isolate MGB vibrations has not performed as well as it was supposed to. HAL has therefore installed active vibration control (AVC) systems in the helicopter to increase comfort by damping vibrations in localised areas like the pilot seat and passenger locations. MGB vibrations continued to be higher than permitted, so destructive failures began to show up at various weak points on the entire transmission and control system over the years. After each crash or accident that revealed control rods had broken, the OEM continued replacing these with stronger ones. The basic problem, viz. the MGB vibration was still not adequately addressed. The last iteration was the modification for changeover to stainless steel rods after the Navy IN 709 ditching. Due to all these modifications the proverbial weak link kept shifting upwards in the control chain, and now the swashplate has become the latest victim. The next stage will probably be to modify the swashplate… and so on. How long can this continue without addressing the basic problems in the design?

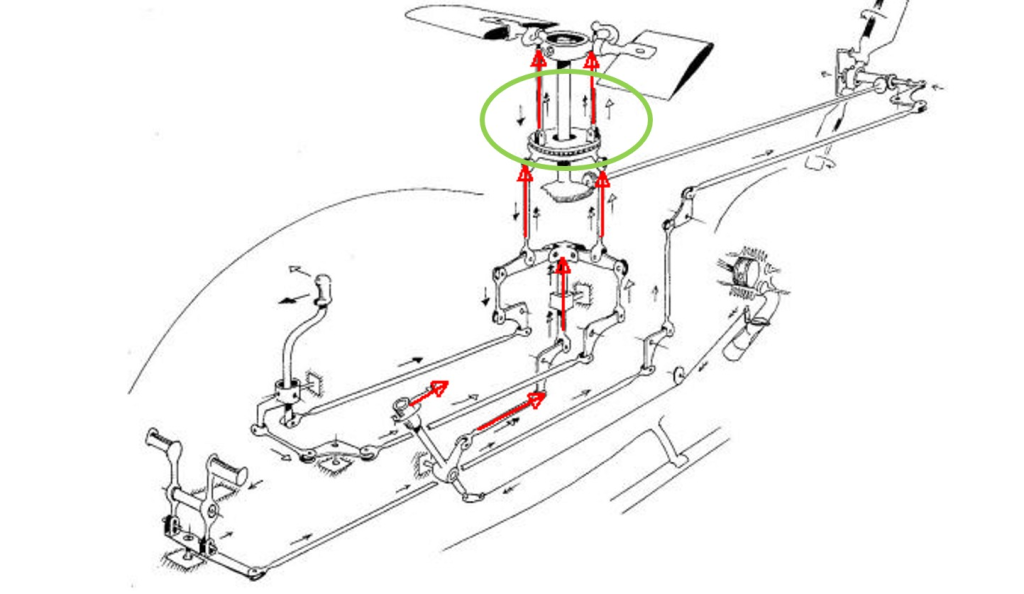

Here is a diagram of a generic control system and the transmission. The control rods are marked in red. The circled part is the pair of swashplates. In the ALH, these rods been failing from time to time.

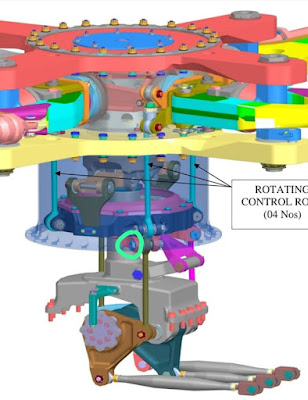

The ALH swashplate arrangement is unique because all the pitch change rods and swashplate are covered by a titanium drum also called the stub shaft. HAL claimed this was a breakthrough in design, because it protected the control rods from battle damage and reduced the height of the mast. No other 5-ton helicopter uses such a design. The mandatory daily inspection of the control rods can never be done on the IDS, so any incipient crack or defect remains hidden until a catastrophic failure occurs. A line diagram of the ALH swashplate is given below with the failed component marked. The portion shaded cyan / blue is the titanium drum and the swashplates as well as control rods are enclosed in it.

Below is a photograph of the IDS. The sealed part with the yellow tape attached is the stub shaft.

The ALH rigid rotor has a very high virtual hinge offset (close to 17%). Due to this offset, the control forces (or the Mast Moment) in turns and manoeuvers can exceed the airframe limits, leading to possible incipient or unrecorded exceedances. Cumulative stresses will lead to catastrophic failures over time.

If one of the rods connecting to the swashplate breaks then the pilot’s movement on the cockpit controls will not be transmitted to the main rotor. The helicopter will crash.

The Mk III MR helicopters use a new version of MGB/IDS that suffer from major problems. At least 10 or 11 IDS / MGBs of the ICG helicopters and some in the Naval ALHs are said to have been rejected and replaced by HAL. This itself should have rung alarm bells, because a manufacturer never rejects an MGB without serious reason. Possibly the same component had failed on all the IDS assemblies. Sources indicate that items such as the quill shaft that drive the cooler fan have had many failures. If undetected, such failures can cause cascading and catastrophic breakdown in the entire MGB because the gear drive is the same.

A Mk III IAF helicopter with new Shakti engines crashed into the water in Bihar while delivering relief materials, and the crew had to be rescued by the very people they supposed to provide assistance to. The Army’s ALH Mk IIIs and Mk IVs have crashed due to control difficulties in the recent years. All these have been relatively new airframes.

When I was in the unit, any problems that we brought up were often glossed over by HAL when discussing them with the headquarters. This would be buttressed with the assurance that things will be fixed, and impressing upon everyone that the ALH was still under development and the problems were a part of the learning process. We never received feedback for corrective actions on defects that we had put up. My helicopter had a CPA (collective pitch anticipator) failure on ground just before takeoff. If this had failed in flight, then both engines would have swung wildly in flight for no apparent reason. HAL dismissed this as a failure of the component without bothering about the seriousness of the effect in flight. It turned out that the CPA bracket was quite shoddily made and hence failed.

Using band-aid for bullet wounds was frequently resorted to. One glaring example is the catastrophic failure of the Tail Gearbox (TGB) on a Navy helicopter in 2005. The helicopter was being ferried from Hyderabad to the ship at Visakhapatnam in July 2005. While landing on the deck, the crew noticed the tail rotor blades were shaking excessively. After a quick shutdown, we saw this horrible sight.

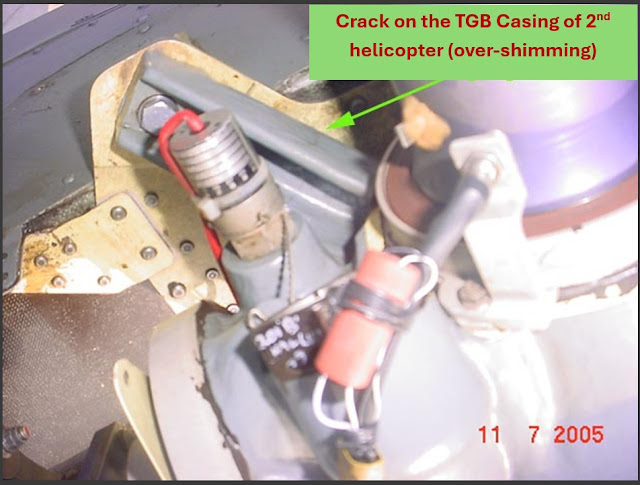

We carried out a thorough inspection of the other two helicopters on the ship and found a second TGB with a crack. Here is the picture:

The HAL team arrived on the ship to replace the blades and TGB that were cannibalised from their production helicopter. We questioned the wisdom of doing this without a detailed investigation to prevent recurrence, especially since two out of three helicopters had cracks on the TGBs. HAL tried to reassure us saying that we should not connect the two incidents. They explained that the second TGB had failed because of over-shimming during installation at HAL, so the reasons were different and no cause for worry. They repaired and flew the first helicopter without any investigation. We in the unit found it very difficult to toe this line of action.

Barely four months down the line in Nov 2005, the first ALH crashed during a ferry from Hyderabad enroute to Ranchi for delivery to the Government of Jharkhand. The TGB had separated from the helicopter and was found lying a few kilometres away from the crashed helicopter. An HAL technical person taken as a passenger was using a kit specially installed only for this flight to monitor tail rotor vibrations. This itself meant that the helicopter was suspect, because such equipment is not used on any routine flight. He gave a warning that the vibrations were reaching the limit, shortly after which the TGB flew away. If HAL had seriously heeded our request in July 2005 for a detailed investigation, this crash in Nov 2005 could have been avoided. The point is that there have been hundreds of such near-misses that could have become catastrophic accidents, but deeper study was always ignored. As an OEM of a developmental helicopter, HAL should have carefully documented each and every failure in every system tracing the defect to its origin to fix the basic issue right from the beginning. Unfortunately, their doctrine of getting the helicopters back in the air, Some How In Time, has ensured that no defect is taken seriously enough. We ended up living from accident to accident with no real safety being ensured. In the case of the November 2005 Jharkhand helicopter crash, investigation revealed many lacunae in the manufacturing and QC processes. Helicopters remained grounded for almost 6 months during this. That helicopter had crashed due to the same reason – the debonded tail rotor blade just like it happened on the Navy helicopter in July!! It is important to note that there is no report of this accident on the DGCA website. Hence there is no public knowledge of why it happened.

Unfortunately, even after the latest accident in Jan 25, the aftermath will likely be some lip service to one-time checks, minor design changes, and attributing blame to training and maintenance at the user. The OEM would most likely again stress on how robust their design is, and that there is really nothing major to fix. Certificates of acceptability from some foreign design team will be waved at us and life will go on. But not for the unfortunate families, and the squadron.

There will also be a lot of talk about how the Services must support indigenisation and local manufacturing. A lot will be said about how HAL is also developing the latest platforms and serving the Armed Forces of India. The public has seen and heard the interaction between top managements of the IAF and HAL at the Aero India Bangalore in Feb 2025, so I will not go into that aspect.

‘Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth”, is a law of propaganda often attributed to one particular Propaganda Minister from the last century.

The MK III and IV on paper have it all- a modern glass cockpit, a great avionics suite consisting of EO pods, machine guns, surveillance radars and all. These are indeed excellent additions to the capabilities. However, this equipment will work well on whichever platform they are installed on, whether land, sea or air. Such equipment does not make the basic helicopter platform inherently fantastic. If the helicopter platform itself is still going through birthing pains, then there is need to retrospect and transform. No amount of embellishments can hide what actually lies beneath. Blind reliance on a single-vendor-supplied machine has led us to this situation; indigenous or not isn’t the issue here. HAL knows that the armed forces are a captive customer base, unable to complain or to go anywhere else to buy helicopters. How then will the OEM be forced to improve his product, if there is no competition and the customers are constrained to buy whatever HAL manufactures?

Yes, the ALH has done immense amount of good work in the high altitude regions, as also during flood and other relief work from Kerala to the Himalayas. There is nothing which can take away from that. The men that operate the machines are fantastic and indeed hats off to their skill, perseverance and grit in getting the jobs done.

The designers have also done a lot of work on making a flying machine. However the sum is less than the total of the parts and this is most unfortunate.

It must be emphasised that HAL exists to support the Armed Forces, and not the other way around. There is a lot written about how the Services must support Atmanirbharta, but at what cost? The Armed forces have a task and that is, to fight the external enemy. They should be able fully trust the HAL product and not have to keep worrying about when the next catastrophic failure will occur from within.

I am not a nay-sayer for the indigenous cause. I am not a supporter of blind import or blind Atmanirbharta. Safety has to remain paramount. All through the period that I flew the ALH, my crew and I remained motivated and eager to fly this Indian designed and manufactured helicopter to its limits. The unit had always given complete feedback both to HAL and to the Indian Navy to see how we can all improve things. Sadly, nobody listened and not enough has improved in the safety and efficiency of the ALH.

Even the CAG report in 2010 has painted a less than rosy picture of the entire project. Those who can read between the lines will realise that there is lots gone unsaid. Has it really made a difference to anybody?

What can now be done?

- First – stop further production, take a pause. The Services must stop accepting any more helicopters from HAL, until all such problems are sorted out for good. The same must apply for any new products from HAL.

- HAL in consultation with the customers, should go back to the data, evaluate each and every failure of every major component, to find out what is the worst cumulative effect that a particular defect can have, if left unnoticed and unchecked. There are countless records of near-misses in which helicopters had a providential escape after a catastrophic failure. This is very important data and must not be glossed over. There are various methods to report serious defects in each service and these also can be starting points.

- Share the crucial data from accident investigations and also from serious defects with all the operators. The ALH is flying both in the civilian and military registration. Hence it is most important that results of all inquiries into serious incidents and accidents from the three services, as well as the defect reports are shared amongst all operators, including the DGCA. Openness is the first step to acceptance and thereafter rectification actions can follow. Operational data can be removed before declassifying the core contents of the military crash reports. To give an example, DGCA has issued 32 Airworthiness Directives on the civil version of the Dhruv with less than a dozen of them flying.

- HAL must talk to the customers and take a consolidated list of their gripe-sheets. They should honestly evaluate the root cause of each point, and see what can be done to fix it both in the existing fleet or during future production.

- Ensure that manufacturing at HAL is done exactly as per the drawings, with precision and care – something that is often lacking.

- Re-evaluate the basic design, and do not put more good money after bad. If for example, the IDS is indeed the main design factor at fault then a high-powered committee must determine how to overcome this once and for all. HAL owes it to the men in uniform that fly, maintain and travel in these machines to make sure that there is 100% safety. Short-cut or quick-fix solutions should not be suggested nor be accepted.

A heartfelt prayer for the unfortunate souls that lost their lives in the crash in January, and for their families.

I hope HAL is listening. I hope that the Services do not get steamrolled into accepting machines that are unreliable and need constant fixing. I hope and pray that there are no more crashes of the ALH due to technical failures.

Jai Hind!!

The author is a helicopter pilot, Qualified Flight Instructor and has about over 6,500 hours of flying. He was the Flight Commander of the first Naval ALH flight and has adequate experience in taking the ALH through all the paces required for Naval requirements. After retiring from the Navy in 2008, he has flown commercial offshore and ashore flights. His views are personal. This post first appeared on Cdr Marathe’s blog here, and is reproduced here with permission. Cdr Marathe has previously written for Livefist here: