PART 2 OF THE INDIAN FUTURE WEAPONS SERIES

On the morning of 7 November 2017, India’s most complicated and troublesome strategic weapon finally delivered after a spate of worrying failures. Worrying, not because such setbacks were uncommon in the testing of weapons. But because the missile’s maker had projected highly ambitious timelines to prove and make available the missile to India’s strategic ground forces. That morning, teams spread between Hyderabad, Bengaluru and the launch site off India’s eastern state of Odisha exhaled for the first time in three years.

But in the three months since that make-or-break test, the Nirbhay program has assumed aggressive new proportions hitherto unknown outside the tiny group of weapons scientists mandated with leading the project. A pronounced push on the program has put the Nirbhay front and centre in the raft of India’s current weapons projects. In simple terms, it now has priority status. Livefist was given access to teams and officials overseeing the the expansion of the Nirbhay program beyond its current confines. In the best traditions of the country’s strategic laboratories, the plans, to say the least, are big.

For starters, in January, the Indian Air Force officially expressed interest in an air-launched version of the Nirbhay, tentatively designated Nirbhay-A for the stand-off air to ground role for its Su-30 MKI jet platform, solidifying its support with a stated interest in acquiring at least 40 systems once it is proven. IAF chief Air Chief Marshal B.S. Dhanoa is understood to have designated a Group Captain-rank officer to be embedded with the new effort and help accelerate development of the air-launched Nirbhay for the area attack role. Both the IAF and DRDO have mutually agreed on a target of 2020 for first drop (weapon release) and 2021 for first test launch.

In an exclusive interview to Livefist, Dr S. Christopher, chief of the Defence R&D Organisation (DRDO) that administers the laboratories developing and testing the Nirbhay, says, “We have begun a study on modifications required on the missile and the aircraft. We will likely remove the booster and a few systems, but largely the weapon will remain the same.”

The team is currently conducting studies to see if the Nirbhay-A can be slung onto the special pylons developed to carry the BrahMos-A, or if they need to be modified. Weight and dimensions won’t be an immediate issue — the Nirbhay is smaller and lighter than the BrahMos. However, they will be using simulations to see if the lighter system needs a powered ‘push down’ before the booster fires, as a safety mechanism. The team hopes to freeze the list of required modifications this year and begin building a prototype Nirbhay-A.

The Indian Air Force recently conducted the first test firing of the BrahMos-A missile from a Su-30 MKI after years in modification delays. The Nirbhay team believes that the heavy-lifting done on the BrahMos will dramatically shorten integration and modification time on the slower, smaller weapon.

“Between Russia, HAL, the DRDO and us, the BrahMos integration has been an exhausting and sometimes frustrating experience,” an IAF officer associated with the BrahMos integration tells Livefist. “Thankfully, the effort paid off. We hope the lessons learned there will help speed up the Nirbhay integration. That is the hope, at any rate.”

But it’s in the Indian Navy’s requirement for the Nirbhay that the missile will really be pushing the proverbial boat out. Simply put, the navy is significantly hungrier for range and wants a version of the Nirbhay that tops its current 1,000 km figures. An Indian Navy source confirmed this, saying the navy is interested in a Nirbhay variant with a maximum range of at least 1,500 km to ‘account for the various types of strike missions that may need to be undertaken with a stand-off system, including land attack’.

At present the navy has pushed interest in a ship-launched version, though interest in a submarine-launched modification may follow. The Indian Navy currently deploys the 290-km range BrahMos supersonic cruise missile from some of its ships and variants of the Harpoon and Klub-S anti-ship/land attack cruise missile from its older submarines and Exocets on its incoming Scorpene-class attack boats. Separately, the navy is in the international market looking to replace its Kh-35 Uran anti-ship missiles with new systems.

“We are conducting a range extension study of the Nirbhay for the navy,” Christopher confirms to Livefist. “We are looking at this in three major ways — optimising fuel efficiency, a bigger fuel tank, and finally an Indian engine which we are designing to be much more economical than the current Russian engine we are using. We had anticipated this requirement and have already begun work on it. The navy is on board with us.”

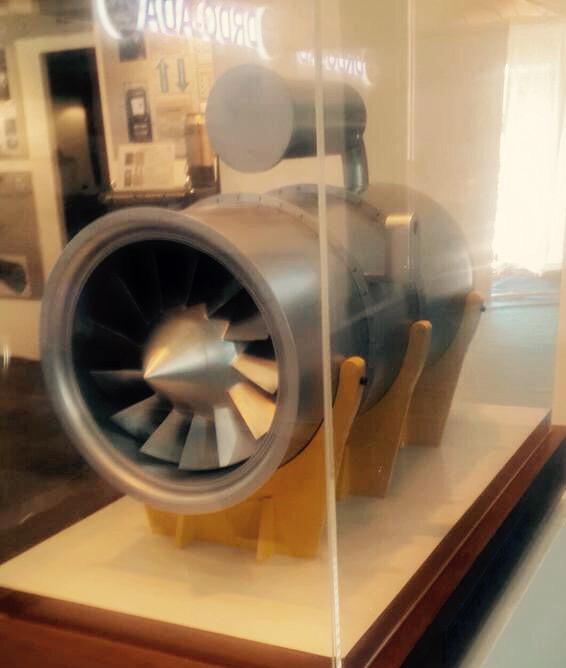

In its five development tests, the Nirbhay has been powered by Russian NPO Saturn 36MT mini turbofan engines. The DRDO’s engine laboratory GTRE (Gas Turbine Research Establishment) is currently steeped in developing a similar indigenous mini turbofan engine called Manik in deep collaboration with the Centre for Propulsion Technology at IIT Chennai and IIT Bombay. Ground runs of the engine are slated to begin this year.

“We are developing the three versions of Nirbhay now. The Manik engine should be ready for testing in two years. By the time user trials begin, we hope to be in a position to offer Manik-powered Nirbhay, at which point the system will be over 95% indigenous. This is a major task for us since this is something we have to prove to the world,” Christopher says.

The Nirbhay project will finally unfurl into a planned Make in India effort with two companies building the weapon system simultaneously for the three services.

“Currently there are ten prototypes, along with work being done by GTRE and the Defence Metallurgical Research Laboratory (DMRL),” Christopher says. “We are also in talks with PTC Lucknow for manufacturing work. We are already in touch with companies in the public and private sector for manufacturing and integration supply work. The whole will be manufactured by an identified agency and they will maintain it for 10-15 years, depending on the service requirement.”

Against India’s pantheon of highly successful and proven long-range ballistic missiles — the Agni and Prithvi series — the Nirbhay is a new fish in every possible way. The 1,000 kilometer range cruise missile flies slower than sound and is powered by a turbofan engine, a vastly different species from the rocket motors that India has mastered on its space and nuclear missile programs. Its makers now hope to dodge headwinds from several quarters — not least shifty service requirements and squeezed budgets — to deliver a cost-effective strategic multi-service weapon.

I dont think the program need any Make In India tag. DRDO will never contract a foreign country to build indigenous weapons.

While all this planning is good, ADE needs to demonstrate that the last successful flight of the Nirbhay was not a fluke and that we actually have a good, reliable system in place. Otherwise we are chasing the two birds without the one in hand…

Hello Shivji,

Can you please add a link to Part 1 of the indian future weapon series also?

Thank You,

Regards